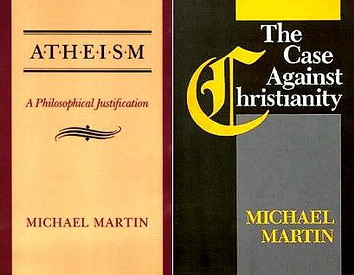

ATHEISM: A PHILOSOPHICAL JUSTIFICATION

BY MICHAEL MARTIN (PUBLISHED 1990 BY TEMPLE UNIVERSITY PRESS. 541 pages)

This book is written for scholarly lay persons and students of philosophy. It is a detailed expose’ of some of the more recent apologies offered by religious philosophers for the existence of a god.

A caveat is in order here. If you are unfamiliar with the terminology and graphics of the symbolic language employed by professional philosophers, then much of this book will be meaningless to you. For example, if modus ponens and modus tollens are unfamiliar terms, then the examples that use them will be like a foreign language.

Fortunately, author Michael Martin does manage to eliminate many of the more technical terms from his book. And, even if the technical nature of symbolic logic is new to you, you will still fund much of value in this book.

The book is divided into two sections, negative and positive atheism. A more thorough explanation of the reasons behind this division would have made the layout more understandable and accessible. The introduction does not offer this, and only briefly covers what is meant by these two terms.

Some of the religious philosophers whose work is covered include Richard Swinburne, Alvin Plantinga, and Bruce Reichenbach. As Martin rightly points out early in the book, their arguments, and those of other like-minded theistic philosophers are not really original at all, but instead based on much earlier, thoroughly refuted arguments. So, while many of their arguments may superficially seem to possess some merit, once the verbal gymnastics are eliminated, the arguments assume a much more familiar form and can be addressed accordingly.

Perhaps the greatest strength of this book is in its lengthy examination of the traditional arguments from evil. Here Martin presents Plantinga’s detailed arguments and then goes on to show how his points are so general that, in actuality, they really have little or nothing to do either with the existence of a god or the problem of evil. Plantinga’s construct is thus laid bare and shown to be seriously flawed since, by taking it at face value, one could just as easily prove the hesitance of witches, leprechauns, or Superman.

In addition, Martin’s dissertation on the free will defense advanced by so many believers is masterfully erudite. He rightly argues that even if a god did give us free will, it is purchased at a heavy price, since we humans have so misused this gift. The countless millions of humans that have suffered and died at the hands of other humans surely must make us question the wisdom of an all-knowing god that would have to insist that all this suffering is offset by our enjoying our freedom, his great gift to us. Is this true morality?

It is interesting to note that Plantinga, when presented with these refutations, fell back on tired old religious cliches such as arguing that perhaps natural evil could be caused by Satan or other evil agents. I feel that this conclusively demonstrates the true nature of most of these religious apologists and their convoluted ruminations: Their ramblings, hiding behind a garb of pretentious intellectual verbiage, only serve as a veneer of what are patently transparent rationalizations.

For the specialist, this book is a necessity. Likewise, non-specialists will find many invaluable pointers to assist them in demonstrating the irrational nature of theistic belief.

Categories: Book Reviews