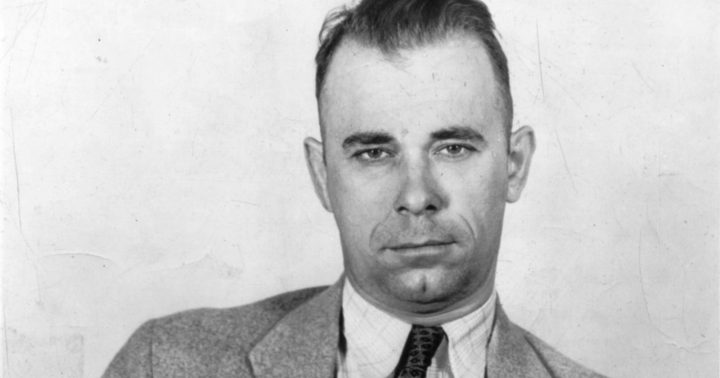

JOHN DILLINGER—WAS HE KILLED, OR DID HE ESCAPE?

My own interest in this case stems from a lifelong fascination with this time period, and in particular with the criminals whose successful activities ultimately led to the growth of the Federal Bureau of Investigation and its head, J. Edgar Hoover. My interest was further stimulated during a 1980 visit to Chicago, when I visited the Biograph theater and spoke to several people who remembered that time very well. One of the people from the theater referred me to a lady who, as a sixteen year old, had lived across the street from the theater where Dillinger was supposedly killed. She informed me that the dead man was a familiar face to her, and had been known to live in the area for a number of years. If true, this contradicts the known facts of Dillinger’s life, since Dillinger had been in prison until some sixteen months prior to his death. At the time, I found her story to be interesting, but assumed she had got her dates wrong, although she steadfastly insisted they were correct. This obviously raises numerous questions. First, how could America’s well-known Public Enemy Number One have managed to escape justice? Where did he live out his life? How could someone as well-known as Dillinger have been mis-identified not only by the coroner’s report, but by the various branches of law enforcement (including the FBI), Dillinger’s own family, friends, and associates, and by the literally thousands of visitors who saw the body at the morgue? If Dillinger wasn’t killed, who was the dead man? Is it possible that a key aspect of American history from this period is outrageously wrong?

The traditional accounts of Dillinger’s life and death need not be recounted here. However, the real history of the Dillinger story, which includes many facts that directly contradict the accepted version of his death, conclusively points to the utter incompetence of the law enforcement officials at that time. This is true from local levels up to the national level. As we will see, the FBI was to prove itself every bit as incompetent as the various local police departments did in addressing the crime wave that followed as the Depression took hold. This will become obvious as we examine the events leading up to, and following, July 22, 1934.

The “American Experience” program discussed Matt Leach, who was Indiana’s Chief of Police at the time. Leach was the first to be given the assignment to capture Dillinger and his gang yet, time after time, his agents arrived too late to make any arrests. On more than one occasion, they arrived only minutes after the gang had made its escape; once they even found cigarette butts still burning at the crime site! As these incidents began to multiply, Leach increasingly came under attack from the public and the media.

Dillinger was not without a sense of humor, and reveled in Leach’s incompetence. He sent Leach postcards and letters, mercilessly taunting the lawman. Dillinger even called him on the telephone. In these early days of Dillinger’s crime spree, his wasn’t a well-known face, either to the public or to law enforcement. There is a well-known photograph of Dillinger posing with his then-girlfriend Mary Longnaker, taken at a carnival. Dillinger passed his camera to a stranger, and asked him to take the snapshot. The grin on Dillinger’s face is no doubt genuine, as the photographer was a uniformed police officer!

At one point, Dillinger saw Leach walking down a street in Indianapolis. Dillinger followed the unsuspecting law official for several blocks. He then telephoned Leach and informed him that, had he so desired, he (Dillinger) could have killed him easily.

In September of 1933, Leach finally hit pay dirt: His agents entered a house in Dayton Ohio where Dillinger was staying with Mary Longnaker. He was arrested without incident. However, he had already laid out plans to sprain three of his friends from Michigan City Penitentiary, some 170 miles away. Dillinger, who had been an inmate there prior to his release in April, 1933, had arranged to smuggle weapons into the prison. While Dillinger was awaiting trial, his friends, accompanied by seven other desperadoes, made their escape on September 26. Yet another indication of the mom-and-pop approach to law enforcement at that time.

Three of these men, Harry Pierpont, Charles Makley, and Russell Clark, formed the nucleus of the new gang. Although Pierpont was the acknowledged leader of the gang, Dillinger’s subsequent exploits made him its most recognizable member; most people, then and since, have assumed him to be the leader. These men soon returned Dillinger’s favor by springing Dillinger from the Dayton prison, killing Sheriff Jesse Sarber in the process. The new gang began its brief but celebrated criminal career by raiding a police station in Auburn Indiana, stealing the supply of weapons, ammunition, and bullet-proof vests stored there. Only in 1930s America could a gang of criminals accomplish such a brazen deed, from a police station no less!

Dillinger’s legendary status soon began to take form. He came to be viewed by many as a modern-day Robin Hood, robbing from the rich banks, although there is little evidence of his giving any of the proceeds to the poor. Nonetheless, the incompetence of the various law enforcement agencies only worked to Dillinger’s advantage. Perhaps the best-known story concerns his escape from the supposedly “escape-proof” Crown Point Jail in Richmond, Indiana. Tradition has it that he poked what seemed to be a pistol in the side of one of the guards and, after disarming him, convinced him to call the other guards, one by one, into the cell block where they were all put behind bars. While some discount the “wooden gun” escape, claiming it was in fact a real gun smuggled in to him (possibly by his girlfriend Billie Frechette), this did not deter the legend makers. Dillinger now began to be transformed from an ordinary criminal into someone assuming almost mythological status. And his criminal career was less than a year old!

In fact, Dillinger posed with the wooden gun and it was known to exist for many years until a souvenir hunter walked off with it. So, embarrassing as it might have been to law enforcement, the story seems to be fairly well authenticated.

As a fitting final touch to this near-miraculous escape, Dillinger drove away from the prison in Sheriff Lillian Holley’s automobile. How he obtained the keys is unknown. For the rest of her life (she died in 1993 at age 103), Holley refused to discuss John Dillinger.

When he drove the car across Indiana into the Illinois state line, Dillinger committed a federal offense, thus enabling the FBI to enter the picture. J. Edgar Hoover contacted Melvin Purvis in Chicago and appointed him as the man to capture Dillinger. Purvis and his agents had little use for Matt Leach or for any local law enforcement officers, thus creating confusion as both sought independently to capture the gang when they should have been working together. Whatever disdain the FBI agents had for local law enforcement, they soon proved themselves to be equally incompetent, if not more so.

By this time, Dillinger had a new gang, as Pierpont, Makley and Clark had been captured. They were subsequently tried and sentenced. Clark received a life sentence (he was released from prison in 1968 when he was found to have terminal cancer) while Pierpont and Makley received death sentences for Sarber’s murder. A month after the Biograph incident, both men attempted to duplicate Dillinger’s famous “wooden gun” escape; they carved out pistols from bars of soap and were leading their way out of the death house when a riot squad opened fire on them. Makley was killed, but Pierpont survived, to be electrocuted the following month. He may have had the last laugh, telling officers just prior to his death that he knew many things about Dillinger that he would never reveal. He died with a smirk on his face. Could he have known something about the Biograph incident that was unknown to others? We will never know.

With his new gang, Dillinger committed numerous bank robberies in South Dakota and Iowa. He was soon to pull off yet another brazen act. Under the very noses of the FBI, he visited his father’s farm for a family reunion. It was there that he posed for a photograph with his wooden pistol. At this gathering, he announced that he would soon be leaving the country and that this would be the last time his family would see him. This is a critical point as we consider Dillinger’s possible escape: Did he possess enough money to leave the country and assume a new identity, or did he simply make this announcement intending that his relatives would report his departure when in fact he remained in the United States?

Part of the answer may be gleaned from the fact that, soon after the reunion, he engaged a doctor to perform plastic surgery on him, altering not only his facial features, but his fingerprints as well. Would he have done this merely to prolong his criminal career in the United States? Given his propensity for theatrics, and given the fact that he had never previously made any effort to hide his identity, this seems unlikely. Dillinger’s crime spree was driven by nothing more than the desire for money; when he had accumulated enough of it, it does not seem far-fetched that he would willingly retire from his increasingly hazardous profession and enjoy the fruits of his labors. Alteration of his fingerprints in particular would have been an important factor if he intended to retire quietly to a non-criminal life. By this time, the pressure on him was immense and the thrill of the chase had lost its appeal to him. If he were smart, which he was, and if he had enough money to begin a new life, it would certainly behoove him to do so.

The family gathering also served to illustrate the incompetence of the FBI, for while it was going on, agents had positioned themselves in the woods behind the house, waiting for Dillinger to emerge. Instead, it was his nephew who came out first, covering his face and pretending to be the fugitive bank robber. The FBI was duped into believing that this was their prey and followed him. Meanwhile, the real Dillinger was able to safely emerge from the house and escape. The FBI, like the despised local officials, had again been outwitted by John Dillinger.

Much worse embarrassment was to come for the FBI. On April 22, 1934, acting on a tip, FBI agents descended on a remote vacation resort in Northern Wisconsin known as Little Bohemia. Knowing in advance of the raid, Hoover at two o’clock in the morning called in the press and announced that Dillinger and his gang were about to be captured. He promised the reporters a big story in the morning. The reporters certainly got a story, but it was not the one that Hoover envisioned. Indeed this was a singularly stupid thing for Hoover to have done, reporting the capture of a criminal who had yet to be captured. Even more so given Dillinger’s proven track record of avoiding capture.

Melvin Purvis himself led sixteen men in a nighttime raid on Little Bohemia. Unfortunately, they had not taken the time to learn the lay of the land. Not even being in possession of something as basic as a map, the lawmen were unaware of the existence of a lake behind the lodge. It was this lake that provided the bandits with their escape route. Eventually, three men emerged from the Inn and got into a car, at which time the agents called on them to surrender. When the men failed to surrender, the agents poured a lethal fuselage into the vehicle, killing one of the occupants and wounding the other two. The three men, who probably did not hear the instructions to surrender, were innocent vacationers, not members of the Dillinger gang. Meanwhile, Dillinger and his gang escaped. To make things even more humiliating for the FBI, gang member Baby Face Nelson, a kill-happy murderer, killed an FBI agent and wounded two others in a nearby confrontation.

As a result of this debacle, Purvis offered his resignation, which was refused. Hoover’s job was likewise in danger, as the Attorney General threatened him with dismissal unless he produced results—and soon. Dillinger’s exploits now had the attention of the entire nation, and President Franklin Roosevelt devoted one of his famous fireside chats to Dillinger. The president solemnly announced that the Federal Government was being mocked for its incompetence and this was completely unacceptable. One day after the Little Bohemia fiasco, Roosevelt announced that he would press Congress to enact six major crime bills designed to give additional powers to the FBI. Hoover and Purvis now had no excuse; they must produce the most wanted man in America. The president of the United States demanded it.

John Dillinger was not stupid. He must have known at this point that the jig was nearly up for him in the states; Hoover would not allow his agency to be the object of scorn as the local officials had already become; they were already being laughed at and derided by the public and press. Hoover felt the pressure put on him by the president’s pronouncements on crime. Dillinger knew that the stakes were simply too high for him and his gang to continue taking the risks that they had heretofore been taking.

Given all this, Dillinger’s next action, as traditionally reported,makes no sense at all. He is alleged to have returned to Chicago with Billie Frechette. Why would the most wanted man in America return to one of the biggest cities in the United States, a state in which he most assuredly would almost immediately be recognized? The fact that Billie was soon captured and eventually sentenced to two years imprisonment underscores the dangers of his being in Chicago. Yet Dillinger, according to traditional history, stayed on in the city that was the primary headquarters of his chief adversary, Melvin Purvis, who conducted his operations from there. Countless leads crossed Purvis’ desk every day; all proved to be false. Dillinger sightings became the order of the day, yet traditional accounts would have us believe that America’s most wanted man remained in Chicago for three months, during the height of the hysteria, under the very noses of the FBI that was sworn to capture him. Either Dillinger had developed a death wish, or he wasn’t there at all.

On the “American Experience” special, historian Claire Potter asks a legitimate question: Why didn’t Dillinger simply leave Chicago? She claims that Dillinger’s finances must have been running out at this time; the extravagant lifestyle he was accustomed to, coupled with the necessity of paying off local law officials, would have necessitated emergency measures. The obvious answer is that Dillinger had already left Chicago or else had never been there at all during this time. There would have been no reason for him to be there, and every reason for him not to be. In addition, Dillinger’s bank robberies had netted him enormous amounts of money, so Potter’s claim that his finances must have been low seems without merit; moreover, there is no evidence that Dillinger lived an especially lavish lifestyle, or that he was paying off local law officials, contrary to Potter’s claims. It is estimated that Dillinger had accumulated as much as three hundred thousand dollars from his various robberies, certainly an adequate amount to provide him with a comfortable lifestyle for years to come.

The Special then recounts the traditional “last” robbery of Dillinger’s gang: the robbery of the Merchant’s National Bank in South Bend, Indiana on June 30, 1934. Traditional accounts state that Dillinger committed this robbery with Baby Face Nelson and Pretty Boy Floyd. However, all evidence points to the contrary. This robbery bore none of the familiar Dillinger trademarks: it was clumsily carried out, and the gunmen seemed unsure of themselves, even firing their weapons unnecessarily in order to impress the patrons with the seriousness of the robbery. Outside the bank there was an enormous amount of gunfire, uncritically reported by the “American Experience” special. This gunfire resulted in the death of one police officer and the wounding of four bystanders. Even though this clumsy attempt was as uncharacteristic of a Dillinger robbery as one could imagine, the TV special (to say nothing of most historians and crime writers), accepting the traditional stories at face value, attempted to rationalize the obvious discrepancies by saying that the gang, realizing that their days were numbered, adopted a “to hell with it” attitude and changed their strategies altogether. This makes no sense at all. Dillinger would never have employed such tactics, or been involved with them in any way; the last thing he wanted was to be re-captured and returned to prison or, worse, face prosecution for murder. Moreover, none of the witnesses of this robbery were able to identify Dillinger, Nelson, or Floyd as the gunmen. While such mayhem would certainly be in character for Nelson, he wasn’t even in the area at the time, having already begun his journey to California. Floyd was known to be in Ohio at the time. So where was Dillinger if not in Chicago? Here is where the facts become murky: While author Jay Robert Nash says Dillinger was on his way to Minnesota to prepare the way for a trip to the West Coast, there is no definite proof of this contention. In fact there is no proof of Dillinger’s presence anywhere in the United States at this point.

Dillinger knew that there was a huge price on his head. In Chicago, a local prostitute named Polly Hamilton, traditionally named as Dillinger’s last girlfriend, had began living with a man who signed his name as “James Lawrence.” Traditional accounts of Dillinger’s life say that he and Lawrence were the same man. Hamilton was employed by a madam named Ana Sage. It was Sage who first approached an FBI agent named Martin Zarkovich, saying she could deliver John Dillinger to them. Her price for providing this information was that she be guaranteed that she would not be deported to her native Rumania.

According to Jay Robert Nash, Zarkovich then reported to his superior that he could, via his connection Ana Sage, deliver Dillinger. However, there was one condition: Dillinger had to be killed rather than taken alive. His reasons for this condition remain unknown, but it stands to reason that if the victim was dead, his corpse could more easily be passed off as Dillinger’s. Zarkovich was unceremoniously kicked out of Police Captain John Stege’s office.

Zarkovich and Sage did not give up. Their next stop was the FBI, appearing in Melvin Purvis’ office with the same offer. Purvis jumped at the opportunity to redeem himself and the bureau. The “hit” was planned accordingly.

On the evening of July 22, Sage and Hamilton led their quarry into the Biograph theater. After the movie ended and “Dillinger” left the theater, the cue was given by Purvis to move in, and the reputed gangster was shot to death—by Martin Zarkovich.

Purvis notified his boss in Washington, who then notified the press that John Dillinger was dead.

However, the evidence that Dillinger was far away from Chicago, and that an innocent man was set up in his place by Sage, Zarkovich, and Purvis, is compelling. Nash relates that the autopsy utterly disproves the dead man’s corpse as being Dillinger’s. Nash contends that the dead man was in fact a small time hoodlum whose name was in fact James Lawrence. The autopsy report alone gives one pause for reflection: The dead man had brown eyes, while Dillinger’s eyes were blue. The dead man also had a serious heart defect, which Dillinger could not possibly have had (given his known acrobatic efforts at leaping over teller’s cages during robberies, in addition to his youthful baseball activities, a sport at which he excelled). The dead man was also shorter and chunkier than Dillinger would have been. Further, in order to compensate for the obvious disparities between the dead man’s features and those of Dillinger, the FBI focused on the fact that Dillinger had plastic surgery, in the hope that this fact would remove any doubts about the corpse’s features being those of Dillinger.

Author Carl Sifakis has made attempts to show that Nash’s points are all invalid and that the dead man was indeed Dillinger. Sifakis points to the fact that coroner’s reports were notoriously inaccurate at this time throughout the United States. He also states that Dillinger had less than ten thousand dollars to live on at the time of his reported death.

The only problem with all this is that it ignores the fact that the autopsy report was conveniently missing for decades, only being re-discovered in the 1970s. This is inexplicable unless the FBI, and by extension the federal government, knew at the time that the dead man wasn’t Dillinger and was thus forced to keep the report from inquiring eyes. Considering the incompetence already exhibited by the Bureau, it stands to reason that they wouldn’t hesitate to go to great lengths to cover up their mistaken killing.

In addition, Sifakis’ report of Dillinger’s financial status is contradicted by numerous other sources, including those who produced the “American Experience” episode on Dillinger.

Another interesting fact is that Sage was soon deported to Rumania, despite the “guarantee” that she would be allowed to remain in the United States. Why would she be deported, unless the FBI had ulterior motives, such was the fear of her “spilling the beans” on the whole charade. If the dead man were indeed Dillinger, why would the law enforcement agencies suddenly renege on their deal with the woman who had brought America’s leading public enemy to them? The only sensible answer is that they were wary of Sage, fearing she might talk, and wanted her as far away as possible.

Nash’s conclusion, that the FBI was simply duped into believing that the dead man’s corpse was Dillinger’s, seems inescapable. Given their track record at the time, it becomes even more of a certainty.

Given the fact that the FBI is such a huge monolithic entity today, it may seem fantastic that there was actually a time when their exploits and methods were so unprofessional and even tragically comical. But the FBI of 1934 was the “new kid on the block” and was far from being the organization it is today. It had yet to prove itself. Indeed, its subsequent meteoric rise is largely the result of its much-publicized crime fighting and gang busting efforts of the mid 1930s—in short a propaganda campaign. It was then that the legend of the crime-fighting FBI, doing constant battle against the evil forces that threaten the American Way, was born.

The argument that Dillinger was addicted to the spotlight and thus would not be capable of fading in to obscurity ignores the fact that for the three months prior to July 22, 1934, he did precisely that. If he could disappear for three months, is it not possible that he could do so indefinitely?

The argument that Dillinger was too famous to have disappeared into permanent oblivion ignores another salient point, namely that countless other criminals had already done so, and have done so since. Western badman Butch Cassidy may have eluded capture; Dr. Joseph Mengele, the Nazi “angel of death” whose crimes shocked the entire world, certainly escaped justice. Again, the plastic surgery issue lends credence to the view that John Dillinger, the most prominent criminal of his time, was ultimately successful in eluding capture and was able to end his days undetected. Even the FBI, in its attempt to pass of Jimmy Lawrence’s corpse as Dillinger’s, was forced to admit how successful the plastic surgery was and how significantly it had altered his features.

Dillinger’s immediate family had everything to gain by continuing the myth that Lawrence was Dillinger. Within a week of John’s death, his father and other family members had taken their act on the road, appearing in shows discussing John’s criminal career—and making significant money in doing so. Like other family members, his younger sister, who survived until 2015, never contradicted the official reports.

While the ultimate fate of John Dillinger may at present be unknown, the fact remains that a major historical revision on the death of one of America’s most interesting criminals is long overdue. What is certain is that, if the real truth were to emerge, today’s politicians and government officials would do everything in their power to discredit the report.

Categories: Miscellanea